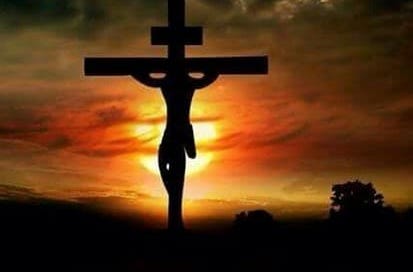

Good Friday is the day when Christians remember the death of Jesus, originally Yeshua, who was later named Christ by the Greeks in an attempt to translate the Hebrew word Messiah (meaning “the anointed one”). Although I do not profess allegiance to any official “denomination”, for me personally this is a time of reflection on the mystery that is at the heart of this ancient religion.

Yeshua dies alone, naked, with a death that Romans reserved for the worst of criminals and slaves. There are several varying accounts of his last moments. According to the Gospel of Matthew, his last words were: “My God, my God, why have you abandoned me?” (in the original “Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani?”). In this post I analyze this sentence in the context of the Christian story of salvation in order to decipher its meaning.

In his last moments Jesus declares himself forsaken. It is a remarkable statement that should give one pause, regardless of whether you are a believer or not. The words indicate a deep sense of abandonment and meaninglessness, even betrayal. If you believe in the divinity of Jesus, God doubts the presence of God. The stark contradiction does not give itself easily to analysis or exegesis. (If you do not believe, it may be an admission that Jesus saw himself as distinct from God)

For centuries the Church has tried to explain away this disturbing statement in their teachings and sermons. Thus one explanation has it that Jesus was praying Psalm 22 which begins with these very words, but later goes on to affirm God’s presence. Philologists know all too well that the Gospels are full of allusion to the works of the Old Testament. But to say that Jesus was only reciting the psalm like a mantra in his last moments is to deny these words their true power and significance.

This will not do.

G.K. Chesterton (Orthodoxy, 1909, 257) tried to provide a provocative answer in which he called Jesus “an atheist for an instant:”

But in the terrific tale of the Passion there is a distinct emotional suggestion that the author of all things (in some unthinkable way) went not only through agony, but through doubt. It is written, “Thou shalt not tempt the Lord thy God.” No; but the Lord thy God may tempt Himself; and it seems as if this was what happened in Gethsemane. In a garden Satan tempted man: and in a garden God tempted God. He passed in some superhuman manner through our human horror of pessimism. When the world shook and the sun was wiped out of heaven, it was not at the crucifixion, but at the cry from the cross: the cry which confessed that God was forsaken of God. And now let the revolutionists choose a creed from all the creeds and a god from all the gods of the world, carefully weighing all the gods of inevitable recurrence and of unalterable power. They will not find another god who has himself been in revolt. Nay (the matter grows too difficult for human speech), but let the atheists themselves choose a god. They will find only one divinity who ever uttered their isolation; only one religion in which God seemed for an instant to be an atheist.

Chesterton’s statement is problematic for several reasons. Firstly, atheists do not address God to say that they were abandoned. Talking to the deity implies existence, which atheists simply deny altogether. Secondly, Jesus is not the only deity who doubts his divinity. For example, Dionysos doubts his divinity and there are a series of myths through which he comes to realize his true identity. Thirdly, his call to the “revolutionists” to choose a god is a political statement that has no bearing on the text and context of the Gospel: it is rather a reaction to the communist revolutions taking place in Chesterton’s lifetime.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Myth and Mystery to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.