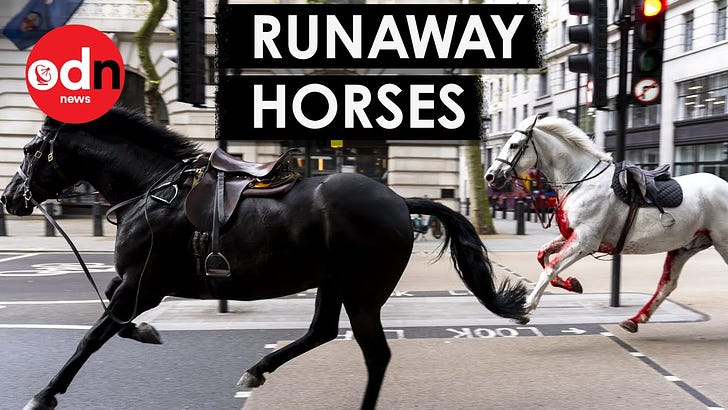

In April of this year, five military horses from the Royal Household Cavalry bolted through the streets of central London, to the consternation of onlookers. Four people were injured and the shock was all the greater for the fact that one of the horses had blood on his legs and chest. While some dismissed the incident as an accident during exercise, oth…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Myth and Mystery to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.